|

Ritualistic RacingUsing Race Track

Magic at Canterbury Park

Susan Stuart Anthropology 472 Dr. Emily Schultz December 20, 2001 I was introduced to the world of thoroughbred horse racing through my mother. When I was a child about 7 years old, she brought my two older brothers and me to Minnesota’s young race track, then known as Canterbury Downs. We spent several hours there, watching the horses race and sitting in the sunny grandstand. I remember very little about the experience except for the fact that my mother placed a bet for me on the last race of the afternoon. Knowing nothing about horseracing other than it was fun to watch, I made my pick based on the jockey. I chose the only female jockey in the race. I remember how excited I was when she won and I was $4 richer. About ten years later in my life, at the age of 16 or 17, I began to regularly attend the horse races with my father and two older brothers (who had re-introduced both me and my father to the sport). My brothers were old enough to wager, but I was not. To make up for this, my father would place a side wager for me and allowed me to hold the ticket and keep the money if my selected horse came through for me. Soon enough, I turned 18 and began to wager with my own money. My older brother, Rob, a constant track companion while he lived in Minnesota and avid handicapper (someone who makes selections of horses on the basis of past performances), once told me that there was no way to beat a day at the track. “Where else can you go and spend $20 for a day of entertainment? You’d lose that in minutes at a casino,” he said to me. For three years, the track became a source of bonding with my brothers as they taught me how to read Daily Race Form—one of the most trusted sources of information on past performances—to gauge horse and track conditions, and analyze records of trainers, owners, jockeys, and of course, the horses. I became a fledgling handicapper. When I turned 21, the race track became a new world to me yet again. I could now sit with a beer as I examined the next race. I was now an adult in the world of horse racing. All that was missing was a cigar hanging idly from the corner of my mouth (I already had a closet full of Hawaiian T-shirts). Strangely enough, the race track had been a bonding place for me. Growing up with two brothers, I was always interested in what they did, making me a veritable tomboy. Remembering the excitement of my first winning ticket, I have eagerly accompanied the males of my family to the race track for at least half of the last five racing seasons at Canterbury. Now that Rob and my father are out of state, I have lost my two main track companions and mentors. This will not kill my race track spirit, however. No matter where I go, I will always make the effort to pull out the Hawaiian shirt, clipboard and the multi-colored highlighter, go buy a copy of Daily Racing Form and visit the closest thoroughbred race track. The original intent of my research was to examine the ritualistic and “superstitious” aspects of the race track atmosphere and its bettors. My first day there as a researcher, I met with the media relation specialist, Joe Anderson. I had his permission to do research and he told me if anyone gave me problems that I should to come to him. He also warned me that I might be mistaken for a reporter, who made bettors nervous. Those words stuck with me and baffled me throughout my research. My fears of sticking out as I took notes soon disappeared, however. It was quite common for people to be carrying all sorts of writing materials and my jotting down notes did not raise any questions. I might have been recording conditions for my own handicapping uses; indeed, I often was. I played a dual role at the race track. My first weekend of research, I did not wager. Each weekend after that however, I took on an observant participant role, wagering to my heart’s content knowing that my older brother would provide support if I needed it. Ironically, the notes I took about conditions at the track for my field notes often pointed to patterns about that day’s racing. The situation that followed is best described in race track vocabulary: On one particularly muddy day, I noticed that a horse that had a certain outer field position was likely to come into the money about 80% of the time. I pointed this out to Rob and he scoffed, but I predicted the winner of the next race due to my notes. Sadly, I only had my brother make a $2 show bet on the runner. In plain English, I noticed that horses in an outer position further away from the inside rail of the track in the gate from which they release were coming in first, second and third place more often than other gate positions. I asked my brother to make a $2 wager that the horse in the particular gate would at least come in third place (show). This means that as long as the horse wins first, second or third place (or “comes into the money” since these are the three positions that are awarded money for the horses and the bettors), the ticket would be a winner. However, show betting does not pay as much as “win” betting, where the ticket will only pay out if the horse comes in first place. Since I was very involved with the races on each day, I was a rather unobtrusive observer. However, I felt that I was being rather obtrusive when I asked to interview people about their wagering habits. Because of this discomfort for both the interviewee and myself, I did not conduct as many interviews as I had initially intended. The dozen that I did conduct, however, were of great help. I will make use of their information in this paper, but I want to make clear that since the pool of peopled I interviewed was too small, it cannot accurately reflect on the opinions of all Canterbury patrons. While I did manage to gather information about practices and rituals performed at the track by bettors, the work eventually came to focus on how the overall horse racing experience creates a viable setting for something I call “race track magic.” As a result, this paper progresses from a discussion of how the atmosphere can possibly set up opportunities for recurring behaviors, to how bettors deal with the amount of information they have, how much of this information they understand and whether this transforms their habits into magic (even though nothing ever progresses smoothly from the beginning to the end, aside from the horses). An important point to note is that I did all of my research on Saturdays and Sundays. As a result, all of the information below may only apply to the weekend. There is also racing on Thursday and Friday nights at Canterbury Park, but since I lacked a car and was at the mercy of my brother, weekends were the only feasible time to do my research. Thus, further research on weekdays would need to be carried out before I could extend my analysis to every racing day. This work draws heavily from Marvin B. Scott’s work The Racing Game, which was written in 1968. It is a truly valuable source of social behavior at thoroughbred race tracks which provided a framework for me to situate my own research.[1] As a final note, at the end of the paper is a glossary of horse racing terms and phrases. Horseracing, as with any other sport, has a language of its own that does not easily correlate with every day conversation. Most of the terms are explained within the paper itself, but for further reference, please refer to the glossary.

The Beginnings and

History of Canterbury Racing By 1982, horse racing had become a very popular sport in North America, with several new tracks being built across the United States. In that year, Minnesota drafted a proposal to create its first pari-mutual (mutual bet) facility. This would be unlike the casinos already in the state, since bettors at a pari-mutual facility directly affect the odds by betting against each other. The more money the bettors wager on a horse, the smaller are its odds to win; as a consequence, a smaller amount is paid back to the bettors should the horse win, place, or show (come in first, second, or third). Conversely, less money wagered on a horse by the bettors results in higher odds and bigger paybacks if the horse should win a first, second or third position. Killingsworth Associates, Inc. drafted the proposal in 1982 for the Minnesota facility and their proposal outlined many of the factors that go into making a successful track, such as the difference between revenue paid in and paid out and the estimated attendance depending on distance from the track. Based on already established markets across the nation, some of their initial projections were: - 160 racing days - An average of 11,484 people attending each race day - Possible employment of 1,224 full-year equivalent positions - An average of $216,272,940 wagered a year on live racing (Killingsworth 1982, 18) In 1982, legislation was passed for the pari-mutual facility and ground was broken in 1984 to begin building the track in Shakopee, a suburb of the Twin Cities area. The next year, 1985, the track opened under the name Canterbury Downs. I have yet to find the actual number of racing days in the inaugural season, but it may have been a 160-day season as the proposal projects. In 1986, Canterbury Downs witnessed its most successful season with approximately $135 million dollars wagered. Then, in 1992, the park shut down for various undisclosed reasons (“History at Canterbury Park” 2001). The

park passed through several different ownerships before it reopened in 1994 for

simulcast betting only. Simulcast

betting is “a simultaneous live television transmission of a race to other

tracks, off-track betting offices or other outlets for the purpose of wagering”

(NTRA 2001). 31,146,742

patrons returned to the facility and wagered $36,299,162 (“History at

Canterbury Park”). The simulcasting

generated enough revenue that the track was able to once again open live racing

seasons the following year, 1995, under the new name “Canterbury Park.” Finally, due to new legislation passed in

1996 that exempts the first $12 million in pari-mutual revenue from a 6% tax,

the park witnessed its first profitable season that year. Consecutive seasons up to 2001 were also

profitable (“History at Canterbury Park”). Canterbury Park became not only the

home of live and simulcast horse racing under its new name, but also, during

the off season a site for concerts, arts and craft shows, and snowmobile

races. In 2000, a few years after legislation

to approve slot machines at the park failed, a card club (which features

several types of poker on the first floor) was approved (“History at Canterbury Park”). However, Canterbury Park and

Canterbury Downs both failed to meet the projections of Killingsworth

Associates, Inc. In 1995, upon the

reopening of the park, roughly $66.5 million was wagered compared to the 1982

projection of $216 million. Even in its

peak year, 1986, the park failed to meet these projections. This discrepancy may have had several causes. Roughly 306,000 visitors came to the park in

1995, compared to the projected 1,837,493.

One possible reason for this is

that throughout the years, the track has reduced its number of racing days from

an average of 120 to an average of 60 (see figure 11). In the 2001 season, the number of racing

days totaled 61. Also, Killingsworth

projected that the average daily attendance to the park would be about 11,484

people. Numbers that large are usually

only seen on special event days such as the Claiming Crown during the recent

seasons. Labor Day weekend can draw up

to 8,000 people on both Saturday and Sunday.

Average attendance on regular Thursday-Friday weeknights and

Saturday-Sunday weekends, however, is much smaller. By contrast, Killingsworth’s

projections for possible employment is slightly lower than the number of people

actually employed at Canterbury, by about 80 positions. During the summer season, while the live

racing season is in progress, the park employs approximately 1,300 people. Before the card club opened, however, the

park employed far fewer people. Three

hundred employees work in the card club (which is open year round, 24 hours a

day) and at the simulcast center.

Employees that are not needed after the live racing season ends have the

opportunity to work at many of the other events that go on at the park during

the off season. Canterbury Park continues to see an increase in wagering

and in visitors with every season, along with a continued profit. It also continues to try to make itself more

appealing to bettors and visitors with new high stakes races every season, the

card club, and many off-season events, all of which have a continual impact on

the surrounding economy. A Day at the Races: A

Typical Weekend at Canterbury Horse racing is an American tradition that is well over 100 years old, and throughout that time, it has established many well-known practices. As it continues on into the 21st century, however, new customs make their way into the system. Canterbury Park, like other horseracing establishments across the country, has a very structured daily schedule consisting of both traditional and new aspects. Regular racing days on Saturday and Sunday are nearly indistinguishable to a bettor; things begin and end roughly at the same times and are often done in the same ways. It is this predictable, structured environment that encourages ritualistic behaviors and the practice of race track magic among attendees. On the weekends, the gates to the park open up at around noon, an hour and a half before the post time (the time at which the horses are led to the gates for the race and all betting on that race is halted). Several people come this early and many spend the time handicapping that day’s races, sitting around the park. They most often sit at the paddock, which is an area where horses are saddled and paraded for spectators to see. At 1:00 PM, the national anthem is sung. Then the track’s announcer Paul Allen, who is also one of the two main professional handicappers employed by the track, hosts a show in the paddock called “Today at the Races.” He is usually assisted by radio KQRS personality, Mike Gelfand, also known as “Stretch.” They tell the bettors their win, place and show picks for each race and what made them choose those horses. This lasts roughly half an hour. During the last fifteen minutes of the show, at roughly 1:10 PM, the horses for the first race are led around the paddock ring so the bettors can take a look at them. They are then led out to the track at roughly 1:30 PM for the first post time. At about ten minutes before each post time, the bugler sounds the traditional horse track tune from out by the winner’s circle, just off the race track. At about three minutes and one minute to each post time, Paul Allen (nicknamed “PA” for the public address system he uses) warns the bettors of the respective time to post, “Three minutes to post time.” Most bettors have placed their bets by this time and are eagerly awaiting the race in one of the grandstand sections. Some bettors, however, wait until the last moment to see how the odds change by watching the boards and monitors that continuously update the odds for each horse, and then they bet accordingly. As the horses are released from the gates at the beginning of the race, Paul Allen announces often in an unmistakable way “And they’re rrrrrracing.” Races, which vary in length, lasts no more than a few minutes. After the results are agreed upon by the judges, the winner complete with jockey on top is led to the winner’s circle, where Kevin Gorg, the track analyst, and second of the two track handicappers, gives a little background on the horse, trainer, jockey, and owner. The bettors then often go cash their tickets if they won, or else discard them if they lost (sometimes in the trash, but mostly on the ground). They then make their way back to the paddock or to the concession stands to wait roughly half an hour until the next race. About 20 minutes before each race after the first, Kevin Gorg analyzes each horse and its odds in the paddock as the horses are led around for the bettors to examine. He will often point out promising and disastrous past performances on the part of the trainer, owner, jockey and the horse. He also reports on conditions of the horses, indicating whether they look hot, sweaty, alert, along with other various body conditions such as whether the tail is off the hindquarters, the ears are perked and so on. After this, the above sequence of bugler, announcements, post time and race are repeated for each race, of which there are usually between 9 and 12 (for a chart breakdown, see Figure 2). With such repetitive behavior, there is a greater likelihood for a bettor to stand or sit in the same place or use the same SAM or teller each time, making those practices into habits and perhaps finally, rituals. Breakdown of an average weekend racing day at Canterbury Park: Noon - gates open 1:00 - national anthem is sung - “Today at the Races” begins from paddock 1:10 - horses for race one are led around paddock 1:20 - bugle sounds 1:30 - first post time while Kevin Gorg analyzes the race and its contenders 10 minutes prior to each race – bugle sounds Figure 2 – Breakdown of an Average Weekend Racing Day The average racing day, however, is not always completely the same. Some features that vary are the number of races run during the day and the various contests that bettors can enter. Many of these features are newer and more interactive parts of spending the day at the races. For example, of the main differences between Saturday and Sunday is that Sunday is “Pepsi Family Day,” and families are encouraged to bring their children to enjoy things other than racing at the park, such as trolley park tours, pony/horse rides and a petting zoo. I was unable to tell, however, if this special promotion increased the number of families at the track on Sundays since on both of the weekend days, entire families, complete with children, were a common sight. This presence of families at the track is different from what Marvin B. Scott found in his study of tracks in 1968. At that time, he found that people often came alone and formed temporary relationships with other bettors while they were there. Today, bettors bring along with them to the track people who they already have established relationships with, whether it is family or friends. A majority of the people I talked to had come with friends or family. There are some common interruptions to the average racing day, such as bouts of bad weather (races can be run in any condition except for lightning) or the injury of a jockey or horse. At the gates at post time, a bettor will witness a horse buck its jockey many times in his or her track career. Decisions then must be made whether the jockey wants to remount, a new jockey needs to be called out, or the horse should be scratched (taken out) from the race. It is not uncommon for post times to be pushed back to accommodate these setbacks. Once these situations are handled, however, things fall back into routine. These setbacks affect the bettor as well; if they usually happen at post time, bettors cannot change their wagers. The track will try to accommodate them, however, by automatically giving bettors holding a wager for a scratched horse the winning price on the first place horse. There are also special events that the track holds. Some of these include days of the Triple Crown races, or Canterbury’s own special event day, The Claiming Crown. Schedules and practices are altered a bit (such as two buglers instead of one), but even on these days, other routines remain identifiable and comparable to those encountered on the average racing day, thereby allowing the bettors to continue their habits and magic practice. Wagering: SAMs and TellersBettors at Canterbury, along with those nationwide, have at least two different ways to make their wagers on races, SAMs and live tellers. SAMs, the first option, are a newer automatic version of the age-old and traditional live teller, which is a second option. SAMs, “Self Automated Machines” or “Screen Activated Machines” are still rather new to Canterbury racing and to thoroughbred racing in general. Approximately four years ago, they first made their appearance as one small cluster near the bathrooms but have since been placed in several more areas of Canterbury Park. They are ATM-like machines where bettors can insert money. They have a touch screen that allows the bettor to choose the amount of wager, type of wager, track, race number, and horse. The SAM then prints out one wager voucher and another for the dollar amount of credit the bettor has remaining. The SAMs do not distribute money. However, a winning voucher can be entered to be added to the amount of credit the bettor has already. Bettors must go to a live teller to cash their vouchers. As an example of modern technology, however, the SAMs can malfunction just like any other computer. When this happens, the bettor either presses a help-button or uses a nearby help-phone to ask for assistance. An employee comes to the bettor, opens up the SAM and either returns the ticket or money that has been entered. Based on my own experience, I have found that this procedure happens relatively fast. But the concern that the response will not be immediate is enough to make other bettors wary, which is one of the many reasons why patrons say they refuse to use SAMs. Another reason why bettors will not use SAMs is because they simply have not learned how. I overheard this many times while standing at the SAMs, as one friend asked another why they didn’t use the machines, usually followed by a statement along the lines of “they’re faster” or “there aren’t any lines.” A 25-year-old male, interviewee #8042, was an example of this. He told me he simply didn’t use the SAMs because he just hadn’t taken the time to learn how. The interesting thing about this, however, is that Canterbury often runs short instructional videos on their in-park network where Paul Allen teaches the bettors to use a SAM. And while a bettor may not be near a TV, the sound from the network is broadcast throughout the grounds as well. Canterbury seems eager to teach their bettors to use the SAMs in order to prevent long lines and bettors potentially being “shut out” (no longer able to make wagers because the race is about to start). Live tellers, on the other hand, have been a part of thoroughbred horse racing for much of its history and dealing with them is the more “traditional” way to make a wager. In the past, this was most bettors’ introduction to wagering at the horse track, although this is no longer the case with the growing use of SAMs. Canterbury still puts an insert in its daily programs that tell a first-time bettor exactly how to make their wager with a live teller: “At Canterbury, two dollars to win on the 2 horse.” On a crowded day, 20 to 30 people will stand in line for each teller available on the first floor, while lines for the SAMs usually number less than 5 people, if there are any lines at all. Interviewee #9022, a 25-year-old male told me that he preferred the live tellers because they were more “personal” and more “traditional.” Many bettors will even have a certain teller who they return to whenever possible for wagering or cashing tickets. Of course, other bettors simply don’t care what they use and will go wherever the line is shortest (usually at one of the several SAM banks located around the establishment). As interviewee #9023 told me, he likes both the SAMs and the tellers, but on that day, September 2nd (Labor Day, one of Canterbury’s busiest days), he was using the SAMs because their lines were much shorter. While some bettors sacrifice tradition for speed, others risk the possibility of being “shut out” for the sake of tradition. The SAMs are not, on the whole, faster than a live teller; the speed of a transaction depends on whether the bettors have fully made up their minds when they wager and on how many bets they plan to make. However, the personal touch of a live teller must offer something to bettors that they do not feel they receive from the SAMs, causing so many of them to stand in long lines to make their wagers. Certainly, the SAMs do not teller the bettor “good luck” with a smile upon their departure as the live tellers do. Variables and

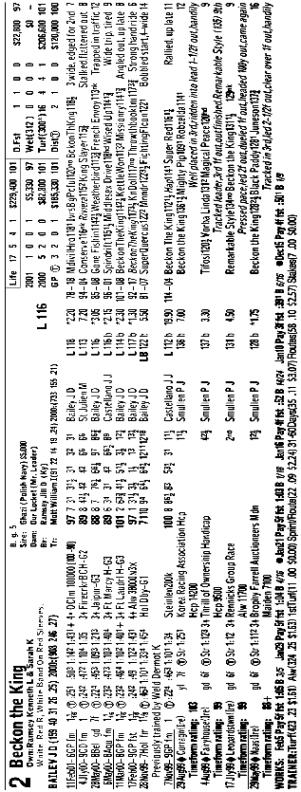

Information at the Track Many different variables and strategies affect the way a bettor will wager his or her money at a horse track. The amount of information a bettor has will directly affect his or her interpretation of these variables to create betting strategies. In horse racing, much of the information is easily attainable by the bettors, whether it is information about a certain horse or information about the track itself. The horse track is not an institution laden with private and mysterious information. The track is usually meant to appeal to urban communities, most often built no more than a half of an hour away from a large city, with the idea of creating an economic motor that will affect the surrounding area in a positive way (Herman 1967, 88). Because of the economic side of horse racing, the government is interested in keeping records about the horse track and many of these reports and records get published to show that the track is not keeping anything secret, and also to increase publicity (Herman, 88). Canterbury Park is an example of this sort of horse track that Robert D. Herman outlines in his article “Gambling as Work: A Sociological Study of the Race track.” A yearly report is published by the Minnesota Racing Commission about Canterbury’s total season handle (the entire amount of money that is wagered in a certain time-frame, which could be a day, a racing season, and even a year), number of racing days and other factors that affected the racing season. Information about the track’s yearly performance, however, does little to help a bettor choose the right horse for a race. Since the information is available to just about anyone with access to a library, however, it does assuage bettors’ worries about whether or not the track is a more trustworthy place to spend their time and money than other gambling establishments such as casinos. The information that does directly affect a bettor’s choice of horse for a race is also easily attainable if one has the time, money, and knowledge. A well respected publication called Daily Racing Form and other more local forms (newspaper-like publications) provides bettors with information on each entry’s recent past races, their breeding, the drugs which the horse is taking, and boundless other information. A bettor has to be willing to spend money on these publications. Even once a bettor has a form, however, it does not do magic on its own. A bettor has to know how to read the information in the forms, because to the uninitiated, they seem to contain a jumble of numbers and nonsensical abbreviations formatted in a nearly unreadable way (see Figures 9 and 10 for samples of forms). Even if bettors have mastered the symbolism of the cryptic racing form, it is up to them to interpret the information. A bettor may look at a horse that the form says has not raced recently and interpret that information in several different ways. Some may feel that this will improve the horse’s chances because the trainer has been giving the horse a break, so it will be fresh and rested once it resumes racing. Another bettor may interpret this information in a negative way; the horse in question has not been kept up in condition and the other horses that have been racing recently have a better chance. Because the information in racing forms is mostly considered reliable (the times and numbers in the forms are factual), most bettors will use it. If only one bettor had the information in the forms, he or she would have a great advantage over the others and the odds would be in his or her favor. But since most bettors have the same access to most of the information, its value decreases. This is why Marvin Scott calls the information bettors receive from forms and professional handicappers “self-destroying information” (Scott 1968, 4). Now everyone knows who looks to be the best candidate in a race and how to wager their money. This self-destroying information can make a tip absolutely worthless if everyone knows and uses it, decreasing the odds and payout on a horse. A bettor must also have a certain amount of time to devote to the information he or she has. Many bettors do their handicapping between the races, a time span of roughly a half an hour. However, there are many handicappers that will sit down with the information the day or morning before the races and make their “picks” before they go to the track. Sometimes this can work to the disadvantage of a handicapper. If the bettor handicaps for a sunny day with a “fast” track (that is, a dry track with optimum speed potential) and there is a sudden thunderstorm before the first race, lowering the track status to “sloppy,” his or her picks will have to be changed in order to factor this in (some horses run better in the mud than others and this can drastically alter a race and its odds, often making it exciting for the fans). The ability to adapt to things such as weather is based on the bettor’s ability to understand information. Another example is a handicapper making a pick and then watching the horse in the paddock as it is paraded around for the bettors to view. If the handicappers see that their pick appears to be “washed out” (sweaty and tired), then they will often look for a new candidate. But the handicapper has to know what sort of physical traits and signs to look for. It is no secret that the horse is washed out if the bettors know what they are looking for. Thus takes a certain amount of knowledge to know what it means when a horse is washed out and to use this information to a bettor’s advantage. To summarize, variables and information are not

withheld from the bettors at a track.

There is no greater mystery surrounding them. It is the bettor that absorbs the information and interprets it

the way he or she desires, based on his or her amount of knowledge about the

situation. There are many tools to help

choose a horse, but in the end, it is the bettor who filters the information

and decides what he or she is going to use and how to use it. Racing Reinforcement One of the problems in trying to understand the behaviors and patterns of a bettor at the horse track is based on the fact that each person can interpret the same set of data differently. Why is it that when one bettor is presented with a set of data, he or she will bet one way and another bettor presented with exactly same data will make a completely different wager? One possibility is that each bettor has been reinforced in different ways by the outcome of the data. One way to examine this phenomenon is through behavioral science’s concept of intermittent reinforcement. Intermittent reinforcement is a concept that explains why subjects will continue to respond to certain situations repeatedly even though they do not receive rewards each time, whereas in continuous reinforcement, the subject is rewarded for each response. Wagering at the horse track is best described as a “variable ratio” experience. Variable describes a discontinuous pattern in reinforcement and a ratio refers to an amount of responses. The bettor is rewarded and reinforced after an unpredictable (variable) number of responses (ratio); the responses could be wagering on a certain type of horse (or even the same horse) or choosing a “winning” teller or SAM, and the reward would be the payout on their decision. However, when subject fails to receive reward for their behavior for too long a time, the repeated behavior’s occurrence begins to decrease until finally, the subject abandons the behavior completely. This is what is called “extinction.” As explained earlier, many bettors will choose or deny a horse with certain conditions. For example, a horse who canters around the paddock looking alert with perked ears and a shining coat can be interpreted by bettors in two different ways. One bettor may feel that this horse, while appearing in good condition, is too eager and is too worked up; therefore, it will use all of its energy before it gets to the track. Such a bettor will prefer a more relaxed horse cantering at a slower pace. A second bettor will choose the first horse precisely because the horse’s condition is believed to show that it is primed for the race while the second slower horse’s paddock performance may result in a lazy performance on the track. Both bettors may have come to their different interpretations through differential reinforcement. If the eager horse wins the race, bettors who favored it will consider this a reinforcement of their betting strategy, and may often look for the same conditions in the next race and try to work them into the matrix of the data that they have accumulated. However, bettors will often not abandon their strategy even if a similar horse does not win the next race, or the race after that. The losing bettor in the situation above will regularly continue to rely on his or her strategy and extend a certain amount of credit even in the face of failure before extinction of the strategy occurs. This seems to be supported by the common belief among bettors Scott describes that the horses and jockeys “owe you money” (Scott, 120). Because bettors believes that they will end up getting their money back at some point because it is “owed” to them, they will continue to bet in the same style without a win for an extended period of time, whether it be days, weeks, or an entire season. Behaviorists have found that the variable ratio reinforcement schedule has the longest extinction period; that is, subjects continue to respond long after they are reinforced because they know that the reinforcement could come at any time (Millenson & Leslie 1979, 107). This holds true for bettors, since they often ride on the belief that at some point the horse will come in and they will get the money that they are owed. After too long a time, however, a bettor will lose faith in his or her strategy and try to create a new one. The same idea can be applied to a certain horse or jockey. If bettors place winning wagers on a certain horse or jockey over a period of time (which could be several seasons), and then suddenly the horse or jockey begins to lose races, bettors will not abandon them immediately. Bettors feel that they are owed money and they fear that the one time that they do not bet on the horse or jockey will be the time that the horse or jockey “comes into the money” (finishes first, second or third). However, bettors do not have to have a winning wager in a race in order to be reinforced. They will be equally reinforced by their experiences as those bettors who held a winning ticket. The bettors who are caught “looking out the window” (that is, not paying attention) while a horse or jockey wins will realize their folly and put their faith back in the jockey or horse, wagering on them once more. During the 2001 season at Canterbury Park, many bettors put their faith in Derek Bell, who was the winningest jockey of that season (Bell had a winning percent of 21.5%, while the average was 13.9%). While Bell certainly didn’t win all of his races, his presence on a horse often was a deciding factor for some bettors. Interviewee #7211, a 25-year-old male, told me that when things looked tough to call in a certain race, it was often a good strategy to bet on Bell’s horse. Bell not only rode favorites to the money, but also many times rode horses with horrible odds into the money. Because of his odds, bettors believed that he was bound to come in for them, and even if he had a losing streak, they believed that he was due for a win at any time. Finally, many bettors may have adopted the habit of using the same teller, SAM, or cluster of SAMs due to their reinforcement, which may in the long run, create the notion of a “lucky teller” or SAM. If a bettor has won several races using the same teller or SAM, he or she may attribute some sort of mystical quality to the person, machine, or location, trying to use it as often as possible. If the bettor loses a race, he or she might blame it on the fact that they had to use another teller that time due to circumstances beyond their control. However, if a certain location, teller, or SAM continues to disappoint them, the bettors may choose a new location to wager. If that teller (or SAM) produces disastrous results as well, the bettor may return to his or her old “lucky teller.” If the new teller issues a winning ticket, on the other hand, the bettor is reinforced that he or she made the correct decision and will use that teller from now on. This behavior may be prone to quicker extinction than wagering on horses, however. Because the teller or the SAM is not the focus of the race, a bettor will not extend them the same credit that he or she will do with a horse or jockey. The tellers do not “owe the bettors money,” nor are they “due for wins or losses.” Because each

bettor is reinforced in different ways, each learns to look at and interpret

the data at the horse track in different ways.

Each set of interpretations is a personal outcome after combinations of

different reinforcements throughout a period of time. While many handicappers and bettors look for some of the same

things, each can vary in interpreting the numerous intricacies of the race

conditions, causing them to favor a certain condition of a horse, a certain

jockey, or even a certain type of name. Customs and Social

Norms at the Race Track In his book, The Racing Game, Marvin B. Scott, talks about several types of typical bettors at a horse racing track. While his book was written in 1968 and some things no longer apply to the modern day race tracks due to technology updates and advances in pari-mutuel gambling, the differences he points out between the two main types of bettors (“the regulars” and “the occasionals”) still hold true in many respects, from their betting habits to their belief in “track magic.” Scott also briefly surmises why horse racing is more of a socially appropriate form of gambling than its casino counterparts. To Scott, a horse track audience is made up of about 1/5 regulars and 4/5 occasionals. Regulars try to attend the track almost every race day with the intention of making a profit. Occasionals come anywhere from once or twice a season to every weekend; however, the occasional bettor does not intend to make profit, rather he/she comes to have a good time and hopefully break even. “If they [the occasionals] should lose—well, that’s what recreation costs; and if they should win—well, that’s what happiness is” (Scott, 116). In many sports, the participants engage in rituals or repeated practices that George Gmelch calls a brand of magic in his article “Baseball Magic” (Gmelch 1999). Horse racing is not exempt from these beliefs. Scott believes a notion of race track magic is another factor that divides the regulars from the occasionals. The regulars have enough understanding of the track, Daily Racing Form, inside tips, and other various sources that they do not rely on rituals or any other sort of magic. Among the bettors Scott interviewed, the regulars seem to be so certain of themselves that they show no signs of anxiety. In fact, they seem certain even of their uncertainty. If the regulars are certain that they are uncertain of a race, they will simply not bet on it. Scott provides an illustrative conversation he had with a bettor concerning this: Interviewer: Who do you like in this race? Subject: (Scrutinizing the Racing Form) Lord Victory looks like the best horse. I: Does he have a good chance? S: Well, it’s really pretty much of an open race, but he’s the best of the lot. I: How sure are you of that? S: You mean, how sure am I that this is a tough race? Oh, I’m sure of that. (The subject did not bet) (Scott, 82) Because of this certainty, these bettors have no need for track magic. Although it is easy enough to argue that their sense of certainty is a false one since many factors go into a horse race, such factors are immeasurable and impossible to put in Daily Racing Form. I will go into more detail about race track magic in the next section. The occasionals, on the other hand, follow a more defined set of beliefs and social patterns. When Scott did his research, it was more than likely that the typical bettor was a male who went to the track alone. Once there, he would form temporary comradeships with other bettors in the same situation. External identities were left behind and new ones were formed briefly in the microcosm of the race track. In the case of present day Canterbury Park, however, nothing is further from the truth. On most racing days, Canterbury is full of groups of people who have come to the track together, men and women equally. Many times, they bring the entire family, more so now that Canterbury has invented “Pepsi Family Day” for each Sunday of the racing season. People still do attend the track alone, but not in the same numbers as in Scott’s 1968 studies. Many of the same social norms still remain, however, and fit into the concept of race track magic. Scott takes the example of cheering for a horse during the race. There seems to be a “well-defined system of etiquette [that] guides behavior of spectators” (Scott, 114). During the first stretch, before the horses take the first turn around the track, spectators are expected to remain seated and quietly root for his/her horse. Once they have reached the backstretch and second turn, it is then considered appropriate to stand up. Only when the horses reach the final stretch, headed for the finish line is it proper to cheer loudly (and often scream) for one’s horse and climb up onto one’s seat to see better. Climbing up on the seats at Canterbury is not a common practice since the seats are apt to break if a full grown adult stands on one for too long. However, the rooting and standing protocols match the behavior at Canterbury. Another social rule is to not ask another bettor how much money he or she has wagered on a bet. Asking about which horse the bettor chose is not entirely appropriate, either, but not troublesome. When asked, bettors may not tell the inquirer which horse they chose for fear that they may jinx their bet. Because the occasional bettor is often not as overly confident of his or her bets as the regular is, such rituals, customs, and social norms appear. Looking at my own data, I believe that all of the people I briefly interviewed were “occasionals.” All of them seemed to be there with friends or family and most said that they were happy as long as they had a good time, whether they made money, broke even, or lost some. Of course, they were much happier leaving the track with more money than when they came, but their day did not depend on this factor since the race track is set up as a way to spend several hours in an enjoyable atmosphere. Horse racing is a multi-faceted sport and this is why Scott believes that it is such a socially acceptable form of gambling appropriate for things such as family outings. The actual horse racing aspect of the game is a rigorous one. It is a world in itself full of horsemen, jockeys, trainers, owners, and breeders. The intensity and layers of involvement of the actual sport helps to disguise the gambling aspect of the game, whereas there is no sport in casino or lottery forms of gambling (Scott, 117). Also, pari-mutuel gambling allows bettors to believe they have more control over their wagering. If they lose, it’s not because the “House” has tried to trick them out of their money. Instead, bettors simply feel they did not take account of all the factors and did not choose the appropriate horse. They believe they will learn from their mistake this time and choose the right horse for the next race, employing new strategies and maybe a bit of magic. Race Track Magic In a seemingly unlikely comparison of two drastically different situations, a tie can be found between Bronislaw Malinowski’s observations on native Trobriand fisherman and Scott’s theories on practicing magic at the horse race track. At the race track, when an individual is uncertain and lacks information, magic is called upon to provide help. In the opposite situation, when information is present and there is a high level of certainty, magic is not required. This use of “race track magic” helps draw the line between the “regular” and “occasional” bettor, as noted in the section above. Malinowski found during his studies in the early 1900s that Trobriand fishermen who go out to open sea where they have little to no control over fishing conditions rely on a system of fishing magic, similar to the way the “occasional” bettor may rely on race track magic. On the other hand, when Trobriand Islanders are fishing in the nearby lagoon “can completely rely on their knowledge and skill, magic does not exist” (Malinowski 1948, 31). This is not unlike the “regulars” who are comfortable with their situation and do not engage in rituals or other magic practices. When circumstances are not ideal or comfortable, “gaps in [an individual’s] knowledge and the limitations of his early power of observation and reason” can result in the use of magic (Malinowski 1948, 90). Because the conditions, such as weather (bad weather that makes fishing in the open-sea impossible may still allow fisherman to use the lagoons), vary in open-sea fishing, they create a more dangerous atmosphere. The Trobriand Islanders use system of complex magic to aid them in their ventures and to “secure safety and good results” (Malinowski 1948, 3). The occasional bettors, like the Trobriand Islanders on the open sea, often lack reliable conditions, experience and information. To make up for this, they follow a more defined set of beliefs and social patterns and often use a brand of race track magic. Repetitive track behavior surfaces in these conditions. The occasional will make every trip from the grandstand to the paddock for each race. Many of them will, if possible, choose the same seat in the grandstand and the same standing spot at the paddock. One man I interviewed (#9021) told me he stood in the same spot at the paddock “religiously”. He also told me that if he was having a bad day, he would go to the rail to “change his luck.” Then, directly and honestly, he admitted to me that he knows that it has no effect, but he continues to do it anyway. From my studies, I found that many bettors often have a “lucky teller” or a “lucky SAM” that they will return to every race. If they are not doing so well that day they will then try a new teller or SAM to try to change their luck (much as #9021 does). If this does not work, they often revert to their original “lucky” teller. One individual (#7221) told me she was highly wary of the new tellers in the 2001 racing season because she did not know or recognize any of them, so she began using SAMs more often. When an occasional must pick a horse, even a well-informed bettor who can fully read Daily Racing Form will sometimes revert to race track magic. Individual #7211 told me that as a side bet, he will often choose a horse if it happens to have a name similar to a person he knows. Another individual (#9024), a 55-year-old woman who had been attending Canterbury since its opening in 1984, will bet on a grey horse (which is not a common color in thoroughbred racing) based only on the fact that it is grey. These magic practices reflect on the bettors’ lack of control over their situation similar to the case of the open-sea Trobriand fishermen. By contrast, fishermen safe near shore are not worried since dangerous weather conditions do not often apply to the lagoons and they use a reliable form of poisoning that has proven successful in generations of experience. Years of the practice have provided a level of understanding and an effective method that makes the fisherman very certain of their safety and ability to catch fish in the lagoon. Thus, the elaborate magic found in much of the Trobriand Islanders’ society is absent. This is strikingly similar to Scott’s idea of “regulars,” who have a level of certainty about their gambling at the race track. The regulars have enough understanding of the track, Daily Racing Form, inside tips, and other various sources that they do not need to rely on rituals or other sorts of magic. Scott found that even while the regular bettors sometimes carried “lucky” objects, they served a purpose other than magic—a man wore his “lucky” brown fedora every day to the track not because he felt that it brought him luck, but because it “was a good place to keep an ‘odds-percentage chart’” (Scott, 85). These things do not bring their owners luck, instead they serve functional purposes. However, because of their repeated appearances and use, they can be easily mistaken for lucky or magical items. Some regulars may have better access to information provided directly by trainers and other horsemen than others (these regulars are often called “insiders”), and certainly the professional handicappers give the bettors the idea that they have information and skills that most do not. This results in the idea of a “tip,” which is information given to a bettor by someone who seems to be more knowledgeable about the races. The people with the “insider tips” share a commonality with the group of Trobrianders named the Kavataria. These natives own and have access to coral patches that allow a fisherman to make a catch in just about any weather and conditions. Thus, “by the ease of their work and their relative independence of weather,” they can provide fish when no one else is able to, again without the use of magic (Malinowski 1935, 17). Both the “insider” and the Kavataria fisherman have access to certain situations and information that others do not, making what they have valuable to the “outsiders.” Just as the valuable fish can be sold to outsiders, insiders at the track often sell tips to bettors in the form of colored sheets with their picks listed on them for each race. For instance, “Jake’s Green Sheet” is sold at Canterbury Park. Conclusion Because of its layout and repetitious cycles

through out the day, Canterbury Park may encourage ritualistic practices and

race track magic similar to brands of magic used not only by the Trobriand

Islanders, but by people all over the world.

The sense of magic and its rituals allow the users to feel as if they

have more control over their situations in life. Choosing a horse or a teller at Canterbury Park is not exempt

from this practice. The amount of

experience and information the bettors have affects whether or not they use

race track magic. I believe that those

patrons that I interviewed, along with many of the seemingly casual bettors

that make the journey to and from the outside grandstand and paddock are mainly

occasionals. It is important to note,

however, that not every bettor easily falls into one of the two

categories. A bettor who is comfortable

enough to not use magic may only visit the track on a few occasions (a regular

in spirit, but an occasional in practice) and vice versa. The study is far from complete. In the future, I would like to have the opportunity to study patrons on the

second and third floors of the grandstand and attempt to find regulars to help

balance out my data. While doing this

research and writing this miniature ethnography, I have found that the

experience has increased my love and fascination with the world of horse

racing. I am thankful to Canterbury

Park for allowing me to do my studies and to the many patrons who I interviewed

and observed. I am also thankful to

Marvin Scott and my brother, Rob Stuart, for being excellent guides along the

way whether they knew it or not. References Cited (1996). Annual Report of the Minnesota Horse Racing Commission. St. Paul: The Commission. “Employment opportunities at

Canterbury.” Canterbury Park Race track and

Card Club. http://www.canterburypark.com/employment/home.html. (19 Sept.

2001). Gmelch, George. (1999). “Baseball Magic.” Anthropology, Sport, and Culture. Ed. Robert R. Sands. Westport: Bergin & Garvey. Herman, Robert D. (1967). “Gambling as Work: A Sociological Study of the Race track.” Gambling. New York: Harper & Row. “History at Canterbury Park.” Canterbury Park Race track and Card Club. http://www.canterburypark.com/geninfo/history.html. (19 Sept. 2001). Killingsworth Associates,

Inc. (1982). The Potential Economic

Contribution of the Horse Racing Industry to the State of Minnesota.

Massachusetts: Killingsworth Associates,

Inc. “Learn

To Read Daily

Racing Form.” DRF.com –

America’s Turf Authority. http://www.drf.com/flash/pp_tutorial.html. (4 Dec. 2001). Malinowski, Bronislaw.

(1935). Coral Gardens and Their Magic: a study of the methods of tilling the soil and of agricultural rites in the Trobriand Islands. Vol. 1. New York: American Book Company. Malinowski, Bronislaw. (1948). Magic, Science and Religion and Other Essays. New York: Doubleday Anchor Books. Milleson,

J.R. & Leslie, Julian. (1979). Principles

of Behavioral Analysis. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc. National Thoroughbred Racing

Association. http://www.ntra.com/press/glossary/glossary.html. (19 Sept. 2001). Scott, Marvin B. (1968). The Racing Game. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company. WWW Links of Interest Related to

Thoroughbred Horse Racing

http://www.drf.com Daily Racing Form http://www.drf.com/free-info.html Daily Racing Form How-To http://www.ntra.com National Thoroughbred Racing Association Glossary Daily Racing FormA daily newspaper containing news, past performance data and handicapping information. Do not use definite article "The" when describing. For example, "According to Daily Racing Form..." (NTRA) form A publication available to bettors that reports on information about horses in each race, such as a horse’s odds, past performances, breeding, whether drugs or blinkers are used and much more (see figures 8 and 9 for samples). handicap (handicapper) To make selections on the basis of past performances. (NTRA) “… in(to) the money” To win, place or show. “looking out the

window” When a bettor is caught off guard by the results of the race because he or she was not paying full attention or did not want to pay attention to the data while handicapping. paddockArea where horses are saddled and paraded before being taken onto the track. (NTRA)

parimutuel(s) A form of wagering originated in 1865 by Frenchman Pierre Oller in which all money bet is divided up among those who have winning tickets, after taxes, takeout and other deductions are made. Oller called his system "parier mutuel" meaning "mutual stake" or "betting among ourselves." As this wagering method was adopted in England it became known as "Paris mutuals," and soon after "parimutuels." (NTRA) place To come in second place. pick(s) A bettor or handicapper’s selections for win, place, and/or show horses in each race. post time Designated time for a race to start. (NTRA) It is at this point in time that all wagering on the particular race at hand is stopped. purse The total monetary amount distributed after a race to the owners of the entrants who have finished in the (usually) top four or five positions. Some racing jurisdictions may pay purse money through other places. (NTRA) SAMSAM stands for “self automated machine” or “screen activated machine.” Automatic wagering machine that accepts cash and winning tickets and places their value onto another voucher. Vouchers cannot be redeemed at SAMs, this must be done at a live teller. show To come in third place. simulcast A simultaneous live television

transmission of a race to other tracks, off-track betting offices or other

outlets for the purpose of wagering.

(NTRA) (to be) shut out When a bettor can no longer make a wager on a particular race, usually at post time. washed out A horse that becomes so nervous that it sweats profusely. Also known as "washy" or "lathered (up)." (NTRA) win To come in first place.

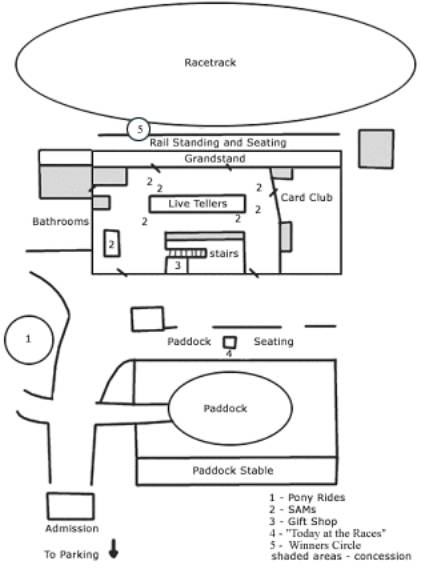

Figure 3 – General thoroughbred horse track layout

Figure 4 – General layout of Canterbury Park track

Figure 5 – Canterbury Park Grandstand

Figure 6 – Sadiedotcom parades through the paddock

Figure 7 – The anthropologist at the finish line

Figure 8 – Bettors at a group of SAMs (Rob is on the left)

Figure 9 – Daily Racing Form Sample (“Learn to Read Daily Racing Form”)

Figure 10 – Canterbury Form Sample

[1] While I touch on many of

Scott’s main points, I encourage the reader to read his work if this paper

sparks some interest. |